I previously wrote about Marty Whitman's insights on Value Investing. One key insight is to focus on what the numbers mean and not just what the numbers are. I cited several examples to highlight this point, and one of them was $GAIA. I got many questions on why $GAIA makes sense as an investment and I am attempting to answer some of them here.

I bought $GAIA when it had just sold off its yoga apparel business. The story was quite simple at the time- Jirka Rysavy, an owner / operator with history of creating wealth, was choosing to focus on streaming business and chose not to participate in tender offer. Most of the value came from cash and building near Boulder, CO. And if the streaming business didn't take off as expected, there was downside protection. $GAIA management also said that they could be profitable at any time with 90 day notice.

So $GAIA at first was the type of investments I am most comfortable with -- where things are so clear that its just simple sum of parts type of math and no complicated model is needed.

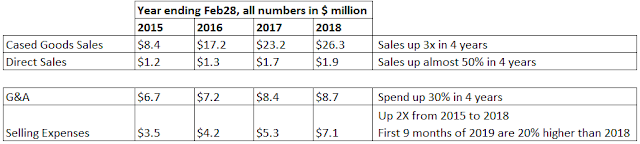

Since then, the subscription biz has grown (66% growth in subscribers from Q217 to Q218), and cash has dwindled (now $41M after recent equity raise). So, now we need to look at whether the growth spend is good investment or torched cash.

Subscription type businesses cannot be valued based on earnings. This is because marketing spend to acquire customers is more like growth capex, but is expensed according to GAAP rules. So its cash outlay at the beginning, and it gets recouped (hopefully) over time. Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and churn are two important metrics here. I recommend this and this article from Tren Griffin ,and this Bill Gurley article to get deeper understanding beyond just mathematical model. Particularly relevant is the following quote from Tren: A business can start out with very high CAC and then have it drop over time (Sirius XM or Netflix) or have relatively low CAC and watch it rise over time (Blue Apron). The case of Blue Apron is particularly illuminating as seen in this excellent twitter thread by @modestproposal1

Blue Apron didn't give churn, so here's a rough cut at GP$/Cost Per Gross Add with 3%/4%/5% churn. Bunch of simplifying assumptions. pic.twitter.com/sT63SNBaPV— modest proposal (@modestproposal1) June 2, 2017

Two key concepts here:

1. Is CAC increasing or decreasing? If company is chasing customers who don't care enough about the product, CAC is likely to increase. CAC is also increasing when many competitors try to bid up the same Google adwords.

2. ARPU, LTV, CAC, churn are all related rather than independent variables. The LTV model is simply a tool to measure how "good" are the investments made by management.

The chart below shows sensitivity analysis based on range of churn rates for $GAIA. My guess is that the churn is closer to 5% because management keeps saying that they keep customer acquisition cost below 50% of LTV. The Marketing expense numbers are from different earning calls.

What's working for GAIA:

1. Cost per Gross Addition (CPGA) is flat to slightly down.

2. Even with close to 5% churn, management statement that they are not spending more than 50% of LTV seems to be correct.

3. They have plans to increase ARPU from the more loyal subscribers by doing live events at their Colorado office space

4. They own the 80% of their content and content production costs are low.

5. They don't have competition in the Truth Seeker area to acquire customers (compared to Yoga where there's other competing apps, and free stuff on Youtube)

6. They will working on getting more organic growth via friend referral (share a video for free with a friend).

There's still lots we don't know. We don't know the churn by type of customer (Truth Seeker, Yoga) and acquisition channel, and if the churn is going up for each cohort or going down. And we don't know the CAC by different customer types. The comments from Management indicate that the Truth Seeker area has lower churn than Yoga area, and so management if focusing on growing Truth Seeker community. Perhaps the best way to understand what's going on is to focus on management's role as investor of capital (Whitman says that this role is not emphasized as much as it should be). To gain new subscribers, they are making investment decisions in the form of marketing spend - Which customers to target? How much to spend for acquiring these customers? Its re-assuring that the people making these decisions have long track record of creating wealth and their own money is tied into it in form of stock ownership. Management even bought more stock in the recent equity raise. This leads me to believe that the management is making good investment decisions. And I am happy to ride along as a stockholder.